About the Book

Add to Your Reading List↓

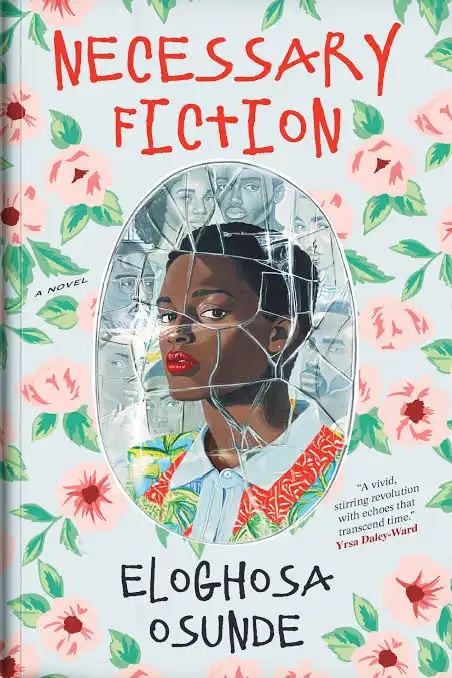

Title: Necessary Fiction

Author: Eloghosa Osunde

Publisher: Masobe Books

Publication Date: 22 July 2025.

Genre: Contemporary Fiction, Literary

Blurb

What makes a family? How is it defined and by whom? Is freedom for everyone?

In Necessary Fiction, Eloghosa Osunde poses these provocative questions and many more while exploring the paths and dreams, hopes and fears of more than two dozen characters who are staking out lives for themselves in contemporary Nigeria.

Across Lagos, one of Africa’s largest urban areas and one of the world’s most dynamic cities, Osunde’s characters seek out love for self and their chosen partners, even as they risk ruining relationships with parents, spouses, family, and friends. As the novel unfolds, a rolling cast emerges: vibrantly active, stubbornly alive, brazenly flawed. These characters grapple with desire, fear, time, death, and God, forming and breaking unexpected connections; in the process, unveiling how they know each other, have loved each other, and had their hearts broken in that pursuit.

As they work to establish themselves in the city’s lively worlds of art, music, entertainment, and creative commerce, we meet their collective and individual attempts to reckon with the necessary fiction they carry for survival.

Review

Immediately I started the book. I knew it wasn’t going to follow the rules. It was so clear. I’d tried reading Vagabond before, but I had to put it down because I wasn’t in the right headspace to navigate what I was reading. But flipping through the opening pages of Necessary Fiction, I came across a cast of characters, and I asked myself—Why do we need a cast of characters? I was thinking, since this is a novel, when I’m reading, won’t I be able to follow and know what’s going on? But now, after finishing Necessary Fiction, I understand why there’s a cast and why it is necessary. There are too many characters. When I say too many, I mean too many.

When I started, I didn’t know who was talking. I was so confused, but as I got into it, I thought Is this what I’ve set myself up for? As I continued reading, I started seeing lines that I immediately felt connected with.

“Some years ago, I used to say none of this is real, but nothing teaches you better than death that life is real. When I’d say that, it was because I thought something being temporary or fleeting or passing made it unreal, less worthy of serious contemplation.”

I said to myself Okay, this is interesting. Because just from my short touch with Vagabond, I already knew this wasn’t going to be typical.

I was lost a lot of the time. It was frustrating, but it was freeing. It was both. Even now, there are some things I don’t remember. Some things just didn’t gel with my reasoning. But I realised it’s not a story you should overthink. I strongly believe this story is meant for you to read freely and pass through. The ones you understand, you take. The ones you don’t, you leave. Whatever resonates with you, you carry with you.

“I see no reason to wear a disguise that wants to take my form without giving anything back in return.”

I had to stop a lot of times just to breathe or reread. My brain couldn’t keep up. This book is like a fever dream, a therapy session, a sermon, a performance piece—it’s everything. It made me want to cry. It made me clap my hands. So many things resonated with me, so many things shocked me, and so many things I couldn’t even relate to. It’s confusing and crazy, but the writing? The writing was good. It was powerful. It’s not for everybody.

My reading experience was chaotic. That’s just it. Chaotic. And because it’s chaotic, it’s an emotional gut punch. It’s confusion, anger, rage, sadness—because you know, for queer lives in Nigeria, they’re always going to face these restrictions from society. More often than not, their families not supporting them. Even when you notice that a family member is queer, they’ll lie and treat you like crap. That denial, that fear—it’s constant. People need to be more accepting of others. But in Nigeria, there’s everything—it’s just so crazy.

“There’s something about losing a dad whose life killed you, you know? There’s no way to explain it. You either know the feeling or you don’t, you get? You feel like you can finally breathe.”

“…you know something I really hate? I hate it when people who have something to salvage in their relationship with their parents act like it gives them virtue. At the end of the day, it’s still your mum. Your father is your father. Sometimes I want to tell people, like, look, I’m so glad you cannot imagine a world where there is simply no relationship to pick up or fix, because things were that bad, things got that bad. But believe it or not, that world exists, and I live there.”

There are so many lines that got me in my chest. I can’t say this book healed me. It didn’t. It forced me to look at some of my wounds. It’s a story that reminds you that friendship is everything. It’s a story that makes you understand the need for community—that you can’t do this life alone. If you try, you’ll go crazy. You need someone. You need your tribe. You need your people—a family away from your family. The people you choose, the ones you say, these are my people, I love them. You shouldn’t be afraid to love and give yourself fully to the people who love you back, the people who’d do anything for you as you would for them.

“Last last, all of us go still die. But if we must live, then shey it only makes sense to love?”

Because there’s a level of comfort to the characters who have worked hard to earn their keep and the others born with privilege, they’re able to do crazy things, so they are the lucky ones who don’t have to face half of the fear or inequality that average queer Nigerians face. It’s a bit far removed from reality, but at the same time, it’s not. Because this is how queer people live—the way they form communities, the way they move, the way they act. The story itself is just so queer.

It makes sense. Yet I like that it doesn’t make sense.

This story is universal, but in a Nigerian way. People who aren’t Nigerian won’t fully understand the queer scene here—the subtext. It’s a different world; others can still relate, sure, but there’s something they might miss. Because underneath everything, this story is a part of Lagos queer culture.

The writing in this book was showing broken people choosing to live, choosing to be unapologetically themselves.

“My body is precious. My body is mine to have, to hold, to belong in, to breathe from, and to forgive. I call back what is mine into this vessel that handles and houses me. My body forgives me and proves this to me by how hard it works for me daily. I forgive my body and prove this to it by how willing I remain to start over again.”

When I turned the last page, I was happy. This book took me on a wild trip. I was scrambling, doing a lot of detective work, because sometimes it went fast, sometimes slow, and it was all so jarring how it jumps from one person to the next, past to future.

“I’m learning that it matters to respect life, to notice it, to notice the body itself, no matter its shape, form, or abilities—as an experience, as necessary.”

I won’t be reading this book again—I know that for sure. But it left me with feelings, thoughts, and vibes. It left me with lines I’ll never forget. Like those wedding vows? I’ll be using those in my own wedding vows one day.

Goodreads ‧ Instagram ‧ Podcast ‧ Services ‧ Storygraph ‧ Tiktok ‧ X